Tuareg, Music, and Islam

- Ivan Branco

- Jan 20

- 8 min read

Iyad ag Ghali: musician, Tuareg, Malian, a man of Islam.

Today: Islamist, Tuareg, Malian.

Ag Ghali’s life is an atrocious parabola, one that plunges downward without any single, decisive psychological cause, nor any purely political explanation—something, therefore, grimly human. And although he never wrote lyrics of bewildering, otherworldly poetic or philosophical depth, and instead composed songs that were, above all, social and political, his existence was nonetheless shaped by the greatest, most luminous and most terrifying of demiurges: God.

His extremism stems, first and foremost, not from the demagoguery of a frightened mind sent into a trance by the idea of God, but from a radicality embedded in art’s very way of being. Not a simple realist depiction, nor some intimate torment or faint Bacchic ecstasy: art is, before anything else, the eruption of the abstract and the metaphysical into the most feral and profane forms of worldly reality. And so even a former guitarist—now a powerful fundamentalist warlord—may hear the Lord’s words more clearly and lucidly than a pope, a monk, or even a scientist.

For all these reasons, the thousands of deaths left in Ag Ghali’s wake across Mali and West Africa become the continuation of a rite: a search, through violence and extremism, for traces of a divine force that surpasses God Himself—one that can be sought and lived only in the desert’s music-filled nights.

Ag Ghali was born with a sensibility tuned to a life of multiple, blazing colours—roles, symbols, and meanings in which beauty and mystery never take on merely dark or simple tones. He is a son not of one Tuareg, but of that very people for whom, in the 1980s and 1990s, he fought fiercely for independence and freedom. The Tuareg have never had a true nation, yet throughout their history they have carried an idea of homeland that has never died.

They wear bright indigo garments; men veil their faces as a sign of honour, respect, and identity. Their society is matrilineal—women not only hold key positions of power, but descent itself follows the mother’s line: children inherit social status and property from their mother rather than their father. And like any truly “barbarian” people worthy of the name, they never surrendered their entire spirit to a single God; they received Him alongside their own natural and divine spirits. In short, a people shaped not by the predominance of reason, but by that of sense—something we Euro-Westerners have only tried to imitate in societies of abundance and consumption, believing that material fullness would lift us to such a level of consciousness and vitality that we could renounce any identity, any centre of gravity, any productive imbalance. A mimicry that, for these peoples—stateless and even without a settled society—means little and proves nothing.

In this landscape, Ag Ghali grows up in a society that is nomadic yet deeply rooted, and he faces the hostility and repression of those African states that have sought—and still seek—to exert strict control over Tuareg existence. Born into a noble and influential family, Ag Ghali, at nine years old, watches his father die as a result of the repression carried out by the Malian government after a failed uprising in the 1960s.

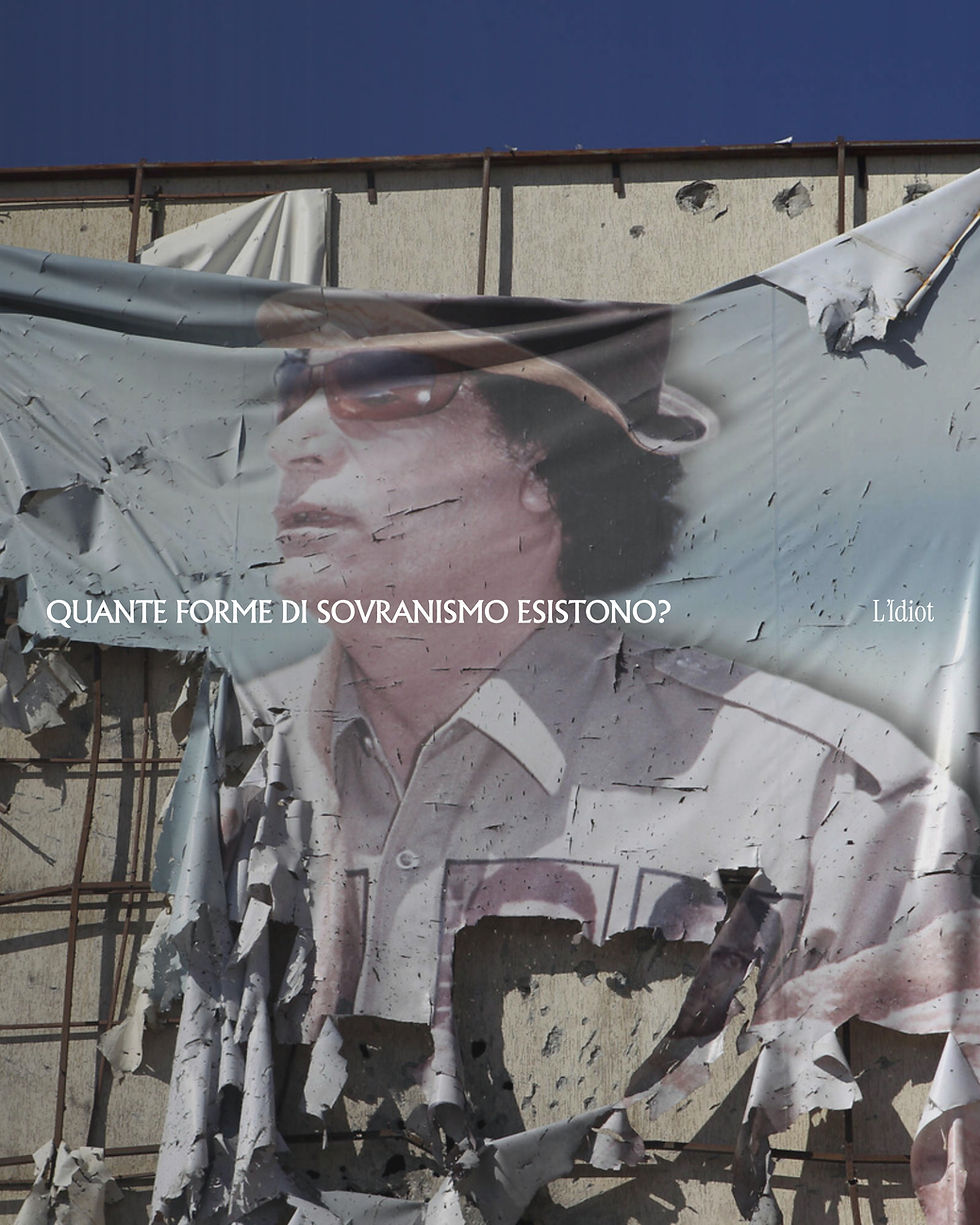

Nurturing contempt, a thirst for revenge, and also a sincere will to free his people, he later joined an army of Tuareg volunteers commanded and sponsored by the Raïs of Libya at the time: Muammar Gaddafi.

Thus begins a tormented yet hopeful journey through North Africa, the Middle East, and back to West Africa, where Ag Ghali and the other volunteers are used by Gaddafi for his political and strategic operations in Lebanon and Chad.

The first stage of revelation was complete: to taste fire, blood, and the ecstasy of conflict and crisis—just as many of our greatest observers and prophets had done before, from Céline and La Rochelle to Jünger, Rimbaud, Nietzsche, Schnitzler, Lichtenstein, Rilke, Trakl, and so on…

And the first step toward the formation of Ag Ghali’s musical group—the Tinariwen—had also been taken. After receiving the task, from Gaddafi, of supervising new Tuareg recruits in a training camp near Tripoli, Ag Ghali meets Ibrahim ag Alhabib.

Like Ag Ghali, ag Alhabib lost his father during the Tuareg rebellion of the 1960s; like him, he wanted to see his people free from foreign rule—not only with weapons, but through a simple act of freedom and art: playing a guitar built from an oil can, a stick, and a bicycle brake cable. Learning, imitating, and then pushing beyond his idols—Elvis Presley, James Brown, Ali Farka Touré, and Arab pop musicians—he and his band created a genre of their own: desert blues. Ag Ghali, too, grasped the importance of music—and of that kind of music—in the struggle for his people’s independence.

For this reason, he himself provided ag Alhabib and his band with everything they needed to carry their work forward: electric guitars and amplifiers, a storage room for rehearsals, even a concrete stage on which to perform. In that period, Ag Ghali also began to collaborate more actively, writing lyrics for Tinariwen, including the song “Bismillah,” which became central to the Tuareg resistance.

Meanwhile, relations between Ag Ghali, his fighters, and Gaddafi grew increasingly strained, until the definitive break in June 1990, when the former moved back to Mali to continue their military and propaganda operations. “By day they raided military posts, and by night they sang by the fire.”¹

After Ag Ghali’s return to Mali and the beginning of the first operations on the ground, victories began to accumulate, until in 1991 Ag Ghali himself signed a peace deal with the Malian government, granting greater autonomy to Mali’s Tuareg—while, in the same period, beginning a long and fruitful collaboration with Bamako.

This collaboration had three key features. First, Malian authorities opened up to Ag Ghali and Tinariwen, who were invited to live in Bamako—Ag Ghali himself having recently received a villa in the capital. Second, cooperation between Ag Ghali and the Malian government deepened, with President Alpha Oumar Konaré personally asking the singer to join diplomatic and institutional trips to Algeria, the United Arab Emirates, and other Arab countries. Third, Ag Ghali’s heavy consumption of alcohol and cigarettes began, along with an increasingly luxurious lifestyle.

And then there is a fourth element that would mark Ag Ghali’s life forever: in 1999, a group of Pakistani Islamic preachers arrived in Kidal, Ag Ghali’s hometown.

Here the second stage of revelation is set: with what eyes to see God, and through what actions to enact, overturn, or erase His Word.

For our mystics, philosophers, and poets, the journey and the final apocalypse have almost always been internal—from Plotinus to Meister Eckhart and Ockham, from Giordano Bruno to Jakob Böhme, Pascal, De Quincey, Baudelaire, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Mallarmé, Artaud, and onward…

But “the East” seeks to feel, see, and value things as they are, in their fullness and reality. The Islamic world often aligns with this, placing at its foundations the absolute rationality and truth of the world as it is—without mystery, without cracks through which other worlds or truths might hide.

So it was for Ag Ghali in his reflections on God and on how to carry His Word.

Ag Ghali moves from being a Tuareg cultural leader to a jihadist chief. As already said, at the end of the 1990s he comes into contact with radical Islamic preachers, draws closer to a highly rigorous form of Islam, yet at first continues to support Tuareg music and the Festival in the Desert—a series of Tinariwen concerts that brought the band international recognition.

Over time, radicalization prevails. Ag Ghali renounces music, accuses the festival of corrupting Muslims, and becomes isolated from young Tuareg people, especially after armed fighters returned from Libya in 2011. Pushed aside, he forms his own Islamist group.

From 2012 onward he leads an insurrection that captures Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal, imposing a reign of terror: banning music, exercising total control over women, enforcing corporal punishment, and committing systematic rape and violence. Despite French military intervention, he is not defeated.

In 2017 he unified various al-Qaeda-linked groups into a new coalition responsible for thousands of attacks and deaths across West Africa. He funds it through gold mines, extortion, and trafficking, exploiting military coups and the withdrawal of Western forces.

Ag Ghali presents himself as a guarantor of local security and justice, but he governs through coercion, feeding a permanent war. Accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court, he remains a fugitive, while Tuareg music survives far from Mali, on international stages.

The third stage of revelation has arrived as well: stripping oneself—stripping the self, the “I”—in order to enter the divine world and hear the voice of one’s Lord, to stain the earth and one’s hands with wine, sound, and blood.

Once again, our hemisphere and the East differ, even as they run in parallel—and we can see it in our own saints and blood-soaked figures too, from Anthony the Great and Saint Olga of Kyiv to Gilles de Rais, De Sade, von Masoch, Aleister Crowley, and so it goes…

Here, however, the narrative of Ag Ghali, Tinariwen, and the Tuareg ends, because the worldly path has run its course. What remains is to look and speak of how such extremism—how radicality itself—claims a necessarily divine nature, in light as well as in shadow, in the very viscera.

Beyond the first three stages mentioned above, a fourth should be added: the awareness of the limitation of the very god one worships, and the act of surpassing him. God is crossed when one becomes the bearer of His Word, which is no longer the Lord’s Word but an absolute Word. The bearer, more or less knowingly, strips himself of God as well, remaining alone with the Word that whirls in his mind and fills his body with children who are damned (for the absence of an external God) and blessed at the same time (for the presence of an inner divinity).

True religion, then, is no longer the cult embodied in worldliness and ritual; it returns to being a primitive, animal element, and human consciousness—Faustian by nature—becomes nothing more than the catalyst that structures and clarifies every religious tendency in man.

As a consequence, all the stages man follows in order to reach revelation will never truly bring him before the God he has always seen, but before the God he has always sought most intimately. And once all trust and belief in the external world is lost, any act performed within it will find no limit and no opposition from divine sense. Artists who do not see God and are not struck by Him are merely men with great creativity and a bit of luck. Those who keep following the distant calls of that far-off god without allowing themselves to be invaded and illuminated will never be seers.

This is the Gordian knot that binds art to extremism—or rather, to radicality. As said above, without liberation from the moral word of a distant god, the world becomes nothing but an immense simulacrum in which God is only a call, a faint and distorted presence—in a word, hallucinatory.

Thus the divine word needs to become flesh, spasm, and to free itself from any law and meaning, becoming pure aesthetics, total representation, absolute act. This process leads to bliss, yes—but not the bliss of a happy consciousness or a solid, human morality. It is the bliss of a rational mysticism and a sovereign, liberated immorality. In concrete reality, this translates into abandoning any illusion of finding inner peace in religion, of believing the divine word to be dawn-like and enlightening, of hoping for a harmonious coexistence between the fierce religious instinct and reason and common sense. And at times, in men more fully erased within their own “I,” it can lead to the ritualization of violence and war—both internal and external—as a way not only to channel and catalyse their desire for the divine, but also to satisfy themselves and reproduce the divine itself. In short: the act is divine in and of itself, no longer only the being toward which it is directed.

In conclusion, the aim is obviously not to defend anything, but to use this figure’s story in order to confront the domination of an external God who keeps harassing us and calling to us from afar, never revealing Himself, leaving us to wander in vain through the deserts of existence and our own interiority.

And so the only act truly capable of throwing that distant god into crisis and laying the ground for the birth of the inner god is to renounce every border, every “elsewhere,” every search in the desert. Indeed, by turning the desert itself into life—and life into a desert—one gains total freedom from any symbol, ethic, code, virtue, dishonesty, until nothing remains but primordial chaos made into a dancing star.

The seer’s ultimate end is, thus, simple: absolute radicality.

Comments