Phenomenology of Populism

- Antioco Lostia

- 2 days ago

- 6 min read

I would have liked to open with a punchy line about populism, a bit like Marx does with capitalism at the beginning of the Manifesto, but that would not only be unoriginal, it would also be anachronistic. Today, in fact, we can no longer speak of a rebirth or an advance of populism, because it has already been reborn, it has already advanced: it has become the new political trend that encompasses everyone—right-wingers, left-wingers, and indecisive centrists alike. Aside from Mamdani or perhaps Polansky, we have seen very few functional left-wing populisms; the ones that gain voters and seize governments every day are instead those on the right. Clearly, the shortcoming of left-wing movements is due to their overly moderate policies and their continued rootedness in neoliberal ideologies—the very same ones we are rebelling against right now.

The neoliberal system has penetrated our society with a subtle violence; without us noticing, it has shaped our minds and our social fabric. And perhaps the most twisted and macabre aspect is that we cannot manage to say “enough”: we talk about making a revolution, but then we order Deliveroo to watch Netflix on the couch. It has built around us—obviously with our help—a glass display case from which we can no longer escape, because by now we are completely dependent on it and subjugated by it. In fact, I allow myself this small personal note—but as a structuralist, I do not even blame us—we fell into a trap without realizing it and began playing by the rules of a game that at first seemed awesome. But in the same way that I look at myself in the mirror every day and fail to notice that I am losing my hair, we fail to notice that we are losing our humanity.

Victims of these toxic dynamics—from suicidal competition to alienating individualism—we collapse in on ourselves in the face of these fictitious houses of cards we have built and call “I.” As pessimistic as it may be, and despite my inability to find solutions, populism paradoxically seems to be the escape route from these individual prisons we have created. It is not just me saying this—let’s be clear—Ernesto Laclau, a post-Marxist, already discussed how populism is a democratic response to a democratic demand advanced by individuals. For him, populism is not only a type of narrative that advances the interests of the people, but also has the narrative task of constructing democratic identity. I think that today more than ever Laclau is right.

Even those shitty neo-fascist right-wing populisms that now govern far too many European countries latch onto an isolated citizen disheartened by society. Populist narratives fill that void we feel inside ourselves. We feel like a castaway in a stormy ocean, and out of nowhere a ship arrives telling you that the real problem is not you but others, meticulously constructing a group identity (something humans need) by antagonizing the outside—migrants, for example. And unfortunately, right-wing populisms are all too good at playing the role of savior. Mamdani is perhaps the first to change course. Clean-cut and young, good on social media—but you already know all that. The truth is that he is perhaps one of the first left-wing politicians in a long time who is actually left-wing: he talks about taxing the rich, rent controls, solid welfare, and so on. In short, he finally applies a politics focused on all citizens, especially those in difficulty crushed by the weight of capitalism.

The real problem—already intuited centuries ago by sociologists like Le Bon—is that the individual within a mass tends to become stupid, a kind of impulsive animal devoid of free will. “Senatores boni viri, senatus mala bestia” (“The senators are good men; the Senate is a bad beast”). Unfortunately, it is a tendency inherent in human beings: when grouped together, we tend to bring out the worst in ourselves. Yet without that cooperation among similar beings, we would probably still be up in trees, fleeing predators or who knows what else.

So perhaps this is another paradoxical aspect: historically we have created very solid group identities—for example religion, the feudal system, or any other socio-cultural-economic movement (the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and so on). For better or worse—don’t misunderstand me. Dogmatic Catholicism, founded on guilt, misled and shaped centuries of human history, but it had one advantage: it connected everyone. In one way or another, everyone had a god over their head, and even if they sinned repeatedly, they were aware of it. With the Nietzschean metaphorical death of God and the decentralization of truth itself, everyone can happily live in their own mental bubble, thinking it is the most correct and enlightened. But I wonder: how can one, in this post-truth world, once again be a society?

To live together, a shared understanding on certain issues is necessary, because only in this way can we coexist without stepping on each other’s toes. Today, after a solid 30 years of dismantling these collective identities and replacing them with a frantic construction of individual identities, we find ourselves incapable even of sharing an identity. And for this reason, what we are experiencing are the most aggressive and violent versions of ourselves, because they feed on our most primordial and animal nature. It is as if we have devolved, and now find ourselves in tribes defending ourselves with clubs or hunting mammoths. In regrouping, we see survival, not living according to a morality that could also be very human, perhaps rooted in the most beautiful aspects of being human, such as empathy and love.

Yet so isolated and frightened, we are like an antelope on the savannah, aware of its condition as prey and of its inability to defend itself. And we human individuals, in this state of animal delirium caused by fear, strike first, attacking so as not to be attacked. This, then, is the most dangerous phase: we group together with the intent of clashing with others, because perhaps this is the only way we currently manage to create groups and identities—through opposition to something or someone. Indeed, perhaps the best way to be someone when you feel like no one is to distance yourself from what you are afraid of becoming. This creation through contrast produces an identity that will always be dependent on its opposite. Consequently, it can never become what it wants to be, because it will always and only be what it does not want to be.

Thus, to give an example like immigration, it will never be resolved, because doing so would destroy the very narrative carved around that fictitious image of the “true” Italian. Identities evolve in the same way a person grows; here we try to be someone we have not been for a long time and can no longer be, and to do so we must force it, rowing against the current. I therefore wonder whether populism can be defined as an antidote, or whether it is simply another spasm of our individualistic self. In my view, it is not a simple spasm, since by now the current and future political landscape is and will be marked by these populisms spreading from India to America to Europe. But then, what will they lead to?

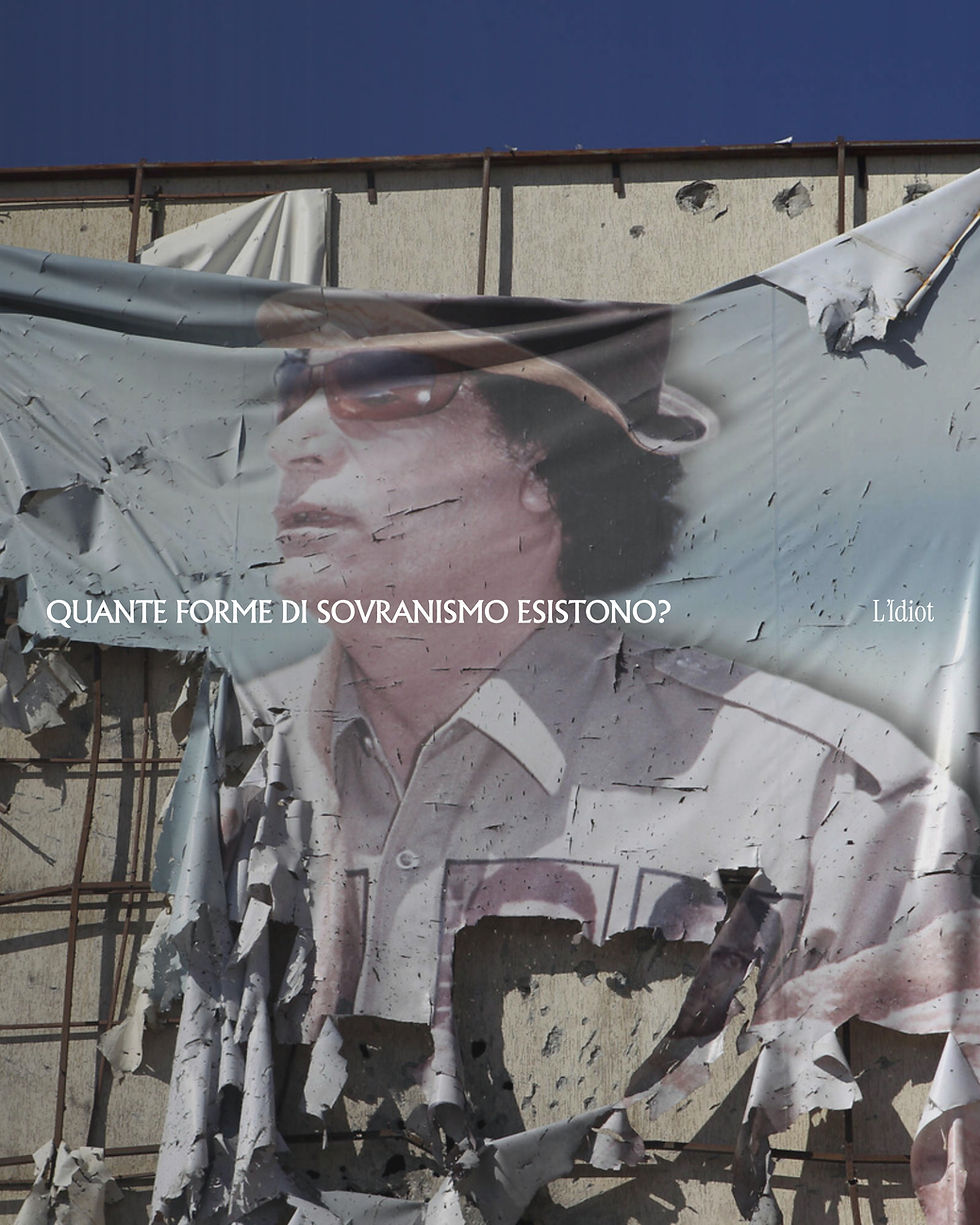

For now, the isolationist measures promoted by populist nationalisms within this post-globalized world are creating a dangerous multipolarity. Paradoxically, the economic interdependence brought about by globalization had prevented many conflicts by making us focus instead on free trade and a massive flow of money. Now, however, as the state returns to realism and acts in an individualistic manner, even applying neo-mercantilist policies, conflicts are just around the corner, and coalitions are more malleable and easily replaceable at the first sign of inconvenience.

I apologize for this somewhat pessimistic ending, but as a Gen Z kid with still a lot to learn, and with a very limited understanding of today’s world and the world to come, it is very difficult for me not to feel beaten down and disillusioned about what lies ahead. Perhaps more out of a sense of obligation toward you than toward myself, I say that the possibility for change exists. Our generation has enormous potential: we are quick, angry, and good at creating networks. We just need to break out of this existential numbness and act, because no one will do it for us. And we all know very well that things are not going the way we would like.

I say this as a sociable and curious person who talks to everyone: what I can say is that political or philosophical orientation hardly matters anymore, because everyone realizes—perhaps in different spheres of life—that there is something rotten afflicting them. The work to be done is above all social: we must all realize that how we feel is not an isolated case, but that we are all, in one way or another, experiencing forms of discomfort. Only then will we no longer feel isolated and defenseless, and instead build that human bond founded on a shared objective that has allowed us, as humanity, to achieve incredible results. Perhaps these are the symptoms before the breakdown—the only real engine of change—and honestly, I hope we get there really fucking angry.

Phenomenology of Populism

Comments